Nodding syndrome, a form of pediatric epilepsy, may result when the immune system tries to fight an infection by the Onchocerca volvulus worm, which causes river blindness. According to a new study, the body reacts to the infection by creating antibodies against the pathogen’s proteins. However, these antibodies also attack a harmless protein present in neurons, triggering nodding syndrome.

The study, “Nodding syndrome may be an autoimmune reaction to the parasitic worm Onchocerca volvulus,” appeared in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Nodding syndrome mostly affects children 5 to 16 years old in the East African nations of Tanzania, Uganda and South Sudan. Symptoms include head nodding, seizures, severe cognitive loss and abnormal growth. According to the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) — which funded the study — nodding syndrome may lead to malnutrition, and patients have died through seizure-associated traumas such as fatal burns and drowning.

Previous studies have linked nodding syndrome to infection by Onchocerca volvulus, but limited evidence links the parasite to brain damage. Black flies spread the worm in certain regions and, as cases of nodding syndrome overlap with these places, researchers hypothesized whether a connection existed between this pathogen and the disease.

They analyzed samples of blood and cerebrospinal fluid from children with nodding syndrome and healthy kids from the same village in Uganda. Results showed that patients with nodding syndrome had higher levels of antibodies against the protein leiomodin-1 than healthy individuals. Leiomodin-1 is usually found in muscle cells, but it was now shown to be present in the nervous system as well.

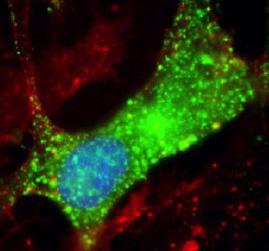

Further analyses showed that leiomodin-1 was present in developing human neurons in culture and in mouse brain tissue, particularly in regions known to be affected in patients with nodding syndrome, such as the cerebellum, the hippocampus and the cortex.

Importantly, when cultured neurons were put in contact with antibodies against leiomodin-1 collected from patients’ samples, they died, whereas removing the antibodies increased neuronal survival.

“These results may ultimately provide a diagnostic test, which can help identify individuals at risk for developing nodding syndrome,” Tory Johnson, PhD, the study’s lead author, said in a news release.

Researchers also found that antibodies that bind leiomodin-1 also recognize proteins from Onchocerca volvulus, linking the parasite to these antibodies. Together, this suggests that nodding syndrome may be a form of autoimmune epilepsy triggered by a parasitic infection. The immune system reacts by producing antibodies against it, which also bind to leiomodin-1, thereby attacking the body’s own neurons that contain this protein.

The team believes children with the disease may benefit from using antiparasitic strategies such as the drug ivermectin, or by receiving immunomodulatory therapies.

“The findings also suggest that therapies targeting the immune system may be effective treatments against this disorder and possibly other forms of epilepsy,” said Avindra Nath, MD, clinical director at NINDS. “Another huge implication of this study is that exterminating black flies and getting rid of the parasite should stop the disorder from occurring.”