Not only abnormal stimulation kills brain neurons in epilepsy, new research shows. It appears that lack of oxygen caused by blood flow abnormalities triggers up to half of nerve cell deaths among epileptics, leading to cognitive problems and even death.

Preventing blood flow deviations in the brain might, therefore, prevent the long-term consequences of the disease.

Researchers also found that spasms in the brain’s tiny blood vessels — which prevent blood from passing through — occur both during seizures and during normal brain function. The findings suggest that epileptic activity lowers the threshold for spasms in blood vessels, in turn, driving neurodegeneration.

The study, “Abnormal Capillary Vasodynamics Contribute to Ictal Neurodegeneration in Epilepsy,” appeared in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Our findings have the potential to transform current understanding of neural degeneration in epilepsy (a wide-reaching and often intractable condition, affecting 50 million people worldwide), as well as its potential treatment,” Stephen Macknik, PhD, the study’s senior author and a professor at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York, said in a press release. “They moreover resolve a historical controversy about the causes and mechanisms of epilepsy, dating back to observations in the 18th century.”

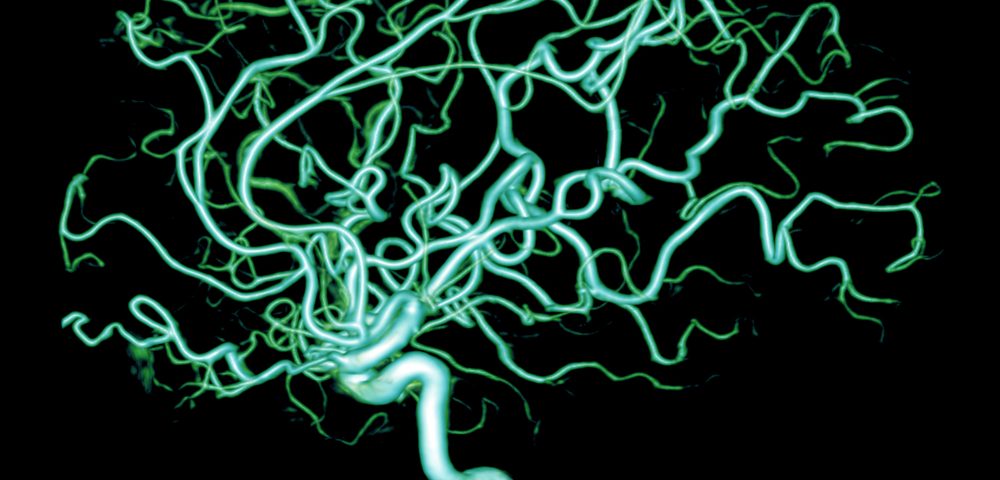

The traditional view of neurodegeneration in epilepsy holds that the abnormal activation of neurons leads to the release of chemical mediators in levels so high they are toxic to neurons. To determine if abnormal blood flow may also affect neuron health in epilepsy, the research team used an advanced imaging technique that allowed them to track blood flow in deeper regions of the brain than was previously possible.

The team focused on the hippocampus — believed to be the site where seizures originate in many patients. Using animal models of epilepsy, the team noted spasms in tiny blood vessels, called capillaries, in the area. The spasms seemed to be triggered by a particular cell type in the blood vessel walls.

Since they found damage related to a lack of oxygen as well as dying neurons close by, they figured that restricted blood flow was to blame. Overactivation of neurons is not related to blood flow. Besides advancing the knowledge of epilepsy disease mechanisms, the study gave added voice to studies showing that capillaries are not mere tubes that passively allow blood to flow through, but actually help regulate blood flow in a region.

Based on their observations, the researchers argue that drugs which regulate blood flow and prevent spasms may improve the treatment of epilepsy to prevent long-term neurodegeneration.

“If this is also the case in humans, it may be possible to prevent or ameliorate the progression of neural damage in epileptic patients via the administration of blood flow-regulating drugs,” authors wrote. “This could be particularly important to patients with medically or surgically intractable forms of epilepsy (i.e. patients with status epilepticus or severe forms of childhood epilepsy, including Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Dravet’s syndrome and Phelan-McDermid syndrome) who are especially vulnerable to neural degeneration.”